Self-assembling robots use flywheels to flick themselves around.

by Casey Johnston

by Casey Johnston

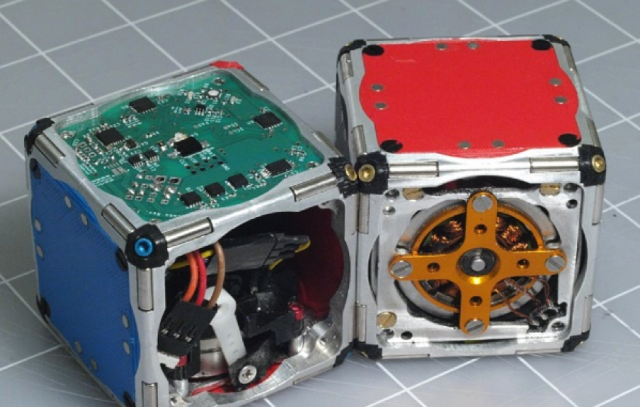

A pair of M-Blocks at rest.

John W. Romanishin, Kyle Gilpin and Daniela Rus

At a certain level of complexity and obligation, sets of blocks can easily go from fun to tiresome to assemble. Legos? K’Nex? Great. Ikea furniture? Bridges? Construction scaffolding? Not so much. To make things easier, three scientists at MIT recently exhibited a system of self-assembling cubic robots that could in theory automate the process of putting complex systems together.

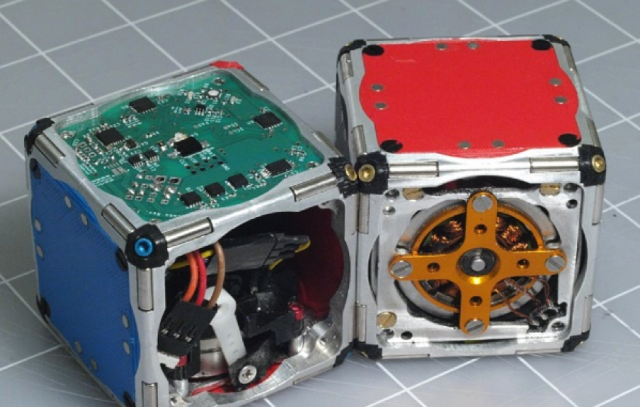

The blocks, dubbed M-Blocks, use a combination of magnets and an internal flywheel to move around and stick together. The flywheels, running off an internal battery, generate angular momentum that allows the blocks to flick themselves at each other, spinning them through the air. Magnets on the surfaces of the blocks allow them to click into position.

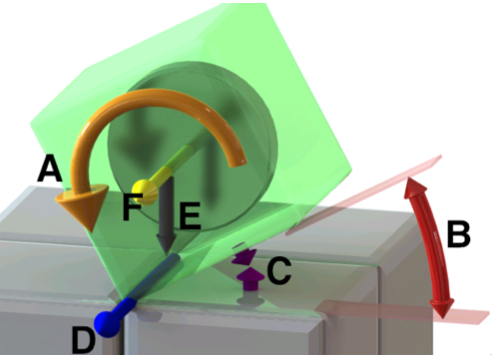

Each flywheel inside the blocks can spin at up to 20,000 rotations per minute. Motion happens when the flywheel spins and then is suddenly braked by a servo motor that tightens a belt encircling the flywheel, imparting its angular momentum to the body of the blocks. That momentum sends the block flying at a certain velocity toward its fellow blocks (if there is a lot of it) or else rolling across the ground (if there's less of it). Watching a video of the blocks self-assembling, the effect is similar to watching Sid’s toys rally in Toy Story—a little off-putting to see so many parts moving into a whole at once, unpredictably moving together like balletic dying fish.

Each of the blocks is controlled by a 32-bit ARM microprocessor and three 3.7 volt batteries that afford each one between 20 and 100 moves before the battery life is depleted. Rolling is the least complicated motion, though the blocks can also use their flywheels to turn corners, climb over each other, or even complete a leap from ground level to three blocks high, sticking the landing on top of a column 51 percent of the time.

The blocks use 6-axis inertial measurement units, like those found on planes, ships, or spacecrafts, to figure out how they are oriented in space. Each cube has an IR LED and a photodiode that cubes use to communicate with each other.

The torque and forces an M-Block experiences from the use of its flywheel. C is the magnetic force between blocks that must be broken for the block to move away from one of its own.

The authors note that the cubes’ motion is not very precise yet; one cube is considered to have moved successfully if it hits its goal position within three tries. The researchers found the RPMs needed to generate momentum for different movements through trial and error.

If the individual cube movements weren’t enough, groups of the cubes can also move together in either a cluster or as a row of cubes rolling in lockstep. A set of four cubes arranged in a square attempting to roll together in a block approaches the limits of the cubes’ hardware, the authors write. The cubes can even work together to get around an obstacle, rolling over each other and stacking together World War Z-zombie style until the bump in the road has been crossed.

The "torque balance" equation that governs the blocks' movement. θ is an angle as a function of time, T(k) is the pure moment, which should be maximized, while the mass m and inertia I are minimized.

The researchers who assembled the project write that the cubes’ design is scale-independent—it could serve as the basis for a system of millions of tiny cubes or a bunch of really big ones. MIT compares their future potential to the liquid steel of Terminator II, but mobile cubes could also be used more generally for repair situations like patching up buildings or bridges in emergencies, for instance.

The authors note that for the same flywheel speed and volume scale, a single large block could generate more torque than a same-sized assembly of many small blocks. In the future, the group hopes to implement bi-directional flywheels that will save the cubes some effort for certain kinds of motion and give them more versatility.

So commercial self-assembling pieces are a long way off. That’s just as well. If we unboxed Ikea cabinets only to have the pieces start inching and flopping toward each other… well, the world is not ready for that yet.

0 comments:

Post a Comment