After two years, its notorious patents were going to a jury. Lodsys blinked.

by Joe Mullin

In 2011, Lodsys seemed like it was working hard to earn the title of the nation's most-hated patent troll by sending threat letters to small developers. At the end of the day, it turns out that Lodsys is one tremulous troll. After settling dozens of cases, the patent-holding firm finally ran into one man who was willing to face it down in front of a jury: Eugene Kaspersky, founder of Kaspersky Lab.

Lodsys decided over the weekend to dismiss its case against Kaspersky with prejudice. Instead of facing a jury, Lodsys will slink away instead. It was an unconditional surrender.

"There was no settlement with Lodsys," Kaspersky's lead lawyer, Casey Kniser, told Ars in a phone interview. "We told these guys from the beginning; we were never going to pay them anything."

Lodsys has claimed that anyone using basic online business techniques such as "in-app" purchases or even customer feedback forms owe it money for its patents. After two years of threats, Lodsys was finally going to have those outlandish claims tested in front of a jury, which was scheduled to assemble in Marshall, Texas on Monday, October 7.

Eugene Kaspersky.

It was the second time in two years that Kaspersky, who has blogged about his disdain for trolls, chose to pay his lawyers instead of the troll.

Interestingly, the other patent troll also sued in East Texas—and also walked away just before trial. That company bore the name Information Protection and Authentication of Texas, LLC, or IPAT. IPAT also sued Kaspersky as part of a large group of defendants in 2008. It tangled with the company's lawyers for years—only to drop its case and walk away without payment weeks before trial in 2012. Just like Lodsys.

"Our suspicion is that these guys don't want to go to trial with anyone," said Kniser. "And that theory is confirmed when they walk away for nothing."

This is the second time in two weeks that Lodsys has avoided a decisive ruling about its business. Last week, the judge overseeing the case refused to rule on a motion by Apple that all its developers were licensed, because Lodsys managed to reach settlements "quickly and cheaply" with the seven Apple developers in this litigation.

The Lodsys worldview: You buy online, you owe us money

Lodsys owns just one "family" of four patents, which was previously owned by Intellectual Ventures. The two patents at issue in the Kaspersky case were 7,222,078 and 7,620,565.

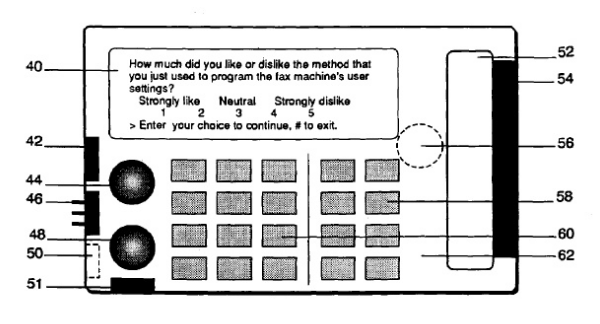

It's a classic troll situation. The '078 patent is a continuation of a continuation application, a way of essentially gaming the system to keep shifting claims while maintaining an earlier priority date. The patent shows a fax machine that asks a user for feedback about how effectively it operates, ranked on a scale of 1-5.

The accused Kaspersky product? The company's "renew license" button, present in many of its software programs, which is nothing more than a hyperlink to an online store. By clicking that button, a customer was giving its "perception" of the product, Lodsys argued, thus treading on the claims of its patent.

Massive amounts of the documents produced by this litigation, unfortunately, remain under seal. Kniser has deposed Dan Abelow, the inventor behind Lodsys—but can't reveal much about what he had to say. Instead, we focused on how Lodsys lawyers portrayed their patent claims in litigation.

The inventor's work was based on work he was doing for Harvard Business School, which was experimenting with early computer-based instruction, said Kniser. "They wanted feedback on how students liked it," said Kniser. "So they asked questions like 'Could you hear the instructor? Could you print the screen that you wanted to print?'"

The prior art had "tons of examples" of people rating machines they had used, said Kniser. For example, there was a patent that described a CD music kiosk that allowed customers to rate the CDs, which the examiner originally said invalidated Lodsys' claims. But Lodsys came back and altered its claims, saying its patent was more like rating the kiosk itself, not the CDs, because it was assessing the "interface" rather than the content.

Another example: while your rating of a Netflix movie wouldn't violate the patent, if you answer an e-mail that Netflix sends you later asking you to rate the picture quality—that's a violation.

That may seem like an obvious and incredibly incremental "advance," but that's exactly the kind of incremental patent examiners often approved, especially when faced with an applicant who can be endlessly persistent. There is no good mechanism to finally reject applicants, and by 2004, Abelow's applications were in the hands of Intellectual Ventures—a massive patent-holding company determined to grow its holdings.

Lodsys' view boils down to this: making a purchase equals expressing a preference about a product, which in turn violates Lodsys patents.

Given that equation, a huge swath of the Internet violates Lodsys patents. It's hard to imagine many interactions that wouldn't infringe, in the Lodsys view. In the Kaspersky case, the company claimed that an intent to buy was enough to infringe.

A shadowy company with unclear ownership has claimed a right to tax basic elements of human culture. And our judicial system is so broken that Lodsys has been able to dodge, for more than two years, ever having those claims subject to a serious legal review. It's a competitive field, but Lodsys is truly the poster child for a broken system.

Courtesy: arstechnica

0 comments:

Post a Comment