Why pay Verizon for tethering when you can set up a Socks proxy?

by Jon Brodkin

Last year, the Federal Communications Commission told Verizon Wireless that it had to stop blocking applications that let cellular customers use their phones as mobile hotspots. Verizon could still require extra payments for tethering from customers with grandfathered unlimited data plans, but the FCC said that consumers with capped plans should be able to use their limited data however they like.

I did a little fist pump when I heard the news. I've had an unlimited data plan for years but knew I might give that up to get my next phone at the subsidized rate and save $450. The time finally came when Apple unveiled the iPhone 5S, which has now replaced my trusty old iPhone 4, which itself replaced my first smartphone, a Motorola Droid.

Although I had to give up my grandfathered unlimited data in order to get a subsidized iPhone 5S, I didn't have to give up my grandfathered pricing. I'm still paying $75 a month (plus $5 or so in taxes and surcharges) for 450 voice minutes, 250 texts, and 2GB of data. Interestingly, I was only able to keep this more favorable pricing by purchasing my phone through Apple's online store. Attempting to upgrade my phone on Verizon's website would have forced me to pay at least $100 a month.

Now that my data plan limits me to 2GB per month, though, I get to tether without paying Verizon extra, right? Not quite. Verizon doesn't actually have to enable tethering to comply with the FCC order, which stems from Verizon purchasing spectrum licenses that forbid application blocking. Instead, Verizon just can't object to third-party tethering applications.

Still, I called Verizon to see if the company would add tethering to my plan without an extra fee. To my total non-surprise, that didn't work because I don't pay for one of Verizon's "Share Everything" plans. The iPhone has a native tethering tool, but it's not visible to the user unless the carrier enables it. Enabling tethering would add at least $20 to my bill each month, which I hoped to avoid. So what were my options?

Not as easy as you might think

Option number one: tethering apps. If I were still using Android, I could tether with something like PdaNet. And even if specific apps aren't available on the Google Play store, Android lets users sideload applications without rooting or jailbreaking.

That's not the case with iOS, of course, and Apple has steadfastly refused to accept tethering apps into its official store. The easiest way for me to tether would be to jailbreak my phone, which I had done with my iPhone 4 before giving up the jailbreak in order to get a newer version of iOS. Waiting for reliable jailbreaks of each new version of iOS can certainly be a pain, but jailbroken phones can use apps like TetherMe without paying an extra fee each month.

The second option was to find an app with hidden tethering capabilities. Occasionally, an app developer creates what looks like a very basic piece of software—a drawing application or a calendar tool—but which actually allows users to share their phone's Internet connection with other devices. Once Apple discovers the app's true functionality, it gets kicked off the App Store. That happened a few months ago with "iRinger," a calendar application that becomes a tethering app when you create an event titled Tethering123:

I bought iRinger for $2 sometime before Apple threw it down the memory hole. Now, I never would have dreamed of using the app's hidden tethering capability while I was still on an unlimited data plan, because that would have violated Verizon's tethering policy.

Wink wink.

20th Century Fox

But now that I have a limited data plan, I can use whatever tethering application I want. I couldn't download iRinger to my new phone from the iOS App Store, but I was able to transfer it from my computer because I had backed up all my applications locally through iTunes.

Using iRinger is not nearly as convenient as the iPhone's built-in tethering system. Instead of creating a Wi-Fi hotspot that any device can connect to, iRinger lets you share your Internet connection through an ad hoc network—provided you're able to follow the 15-step list of instructions.

First, you have to set up an ad hoc network on your Windows or Mac computer. You need to change the IP address and subnet mask on both the computer and phone.

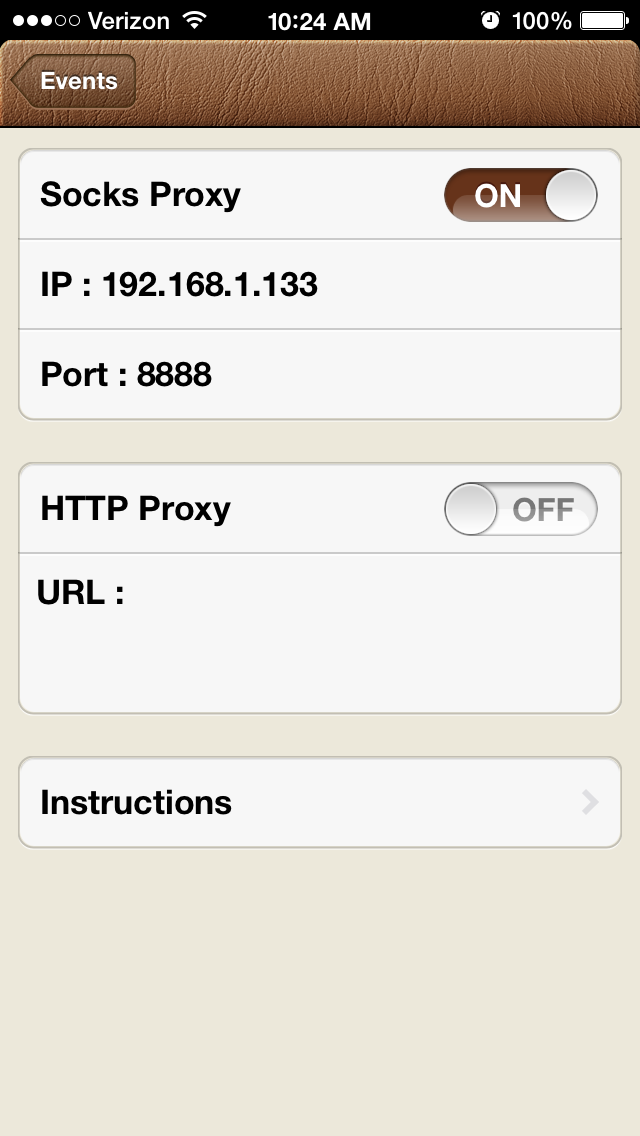

After that's done and your phone can join the network, iRinger creates a Socks proxy or HTTP proxy that will let your computer surf the Web using the phone's cellular data. It works very well.

Sharing the connection with an iPad is much trickier—it even requires you to change your iPhone's language from English to French, and I never quite got it working. But all I really need is occasional tethering to my laptop when I'm without Wi-Fi and need to get some work done.

Unfortunately, iRinger won't help future tethering users unless they happened to purchase it during the short time that it was on the App Store. The only advice I can give is to do an occasional Web search for apps with hidden tethering capabilities. If history is any guide, one is bound to pop up sooner or later, but you need to be quick. (A third-party service also promises tethering for $30 a year without a jailbreak by using an HTML5 browser-based client instead of an app, but I haven't tested it.)

Of course, I'd like a better tethering system myself, and I'll keep my eye out for new applications and iOS 7 jailbreaks. For now, though, I'm in good shape and Verizon can't object to my method of tethering.

But this little exercise does illustrate the absurdities wireless customers often face just because they're trying to use the data they pay for each month. The next time I'm in an airport and can't get a good Wi-Fi connection, I will whip out my phone, get myself online, and realize for the millionth time how amazing technology is—even if my wireless carrier makes it harder to use or more expensive than it should be.

0 comments:

Post a Comment