Apple delivers improvements, but not the ones the iMac needs most.

More than a year and a half passed between the introduction of Apple's 2011-model iMacs and the refresh that replaced them late last year, but the changes you got for waiting were reasonably substantial. The computer got much thinner, lost a few pounds, and ran much cooler and quieter than previous models, and it also got a decent internal upgrade courtesy of new Ivy Bridge CPUs from Intel and dedicated Nvidia GPUs.

Less than a year passed between the introduction of the 2012 iMacs and this year's quiet refresh, and the changes are accordingly much smaller. The 2013 iMac's new changes are all internal—slightly upgraded CPUs and GPUs, a new 802.11ac Wi-Fi adapter, and a switch from SATA to PCI Express solid-state drives round out a refresh that makes absolutely no external changes to last year's chassis. If you were waiting for a Retina iMac to be released this year, your best bet is to keep on hoping.

Still, we've got the $1,299 base model in for testing. And if you didn't buy a 2012 model, is there any one upgrade that will encourage you to buy a 2013 model instead, or should you be waiting for a more drastic upgrade?

|

| Meet Apple's 2013 iMac. It's a whole lot like Apple's 2012 iMac. |

Body and build quality

The 2013 iMac is externally identical to the 2012 model right down to its odd trapezoidal box and its wireless mouse (or trackpad) and keyboard, but we'll recap for those of you with older models. Like last year's iMac, the new model is extremely thin around the edges and bulgy in the back. All of the back-mounted ports remain as annoying as ever to reach around and find, but you get the same number of them as you did last year: one gigabit Ethernet port, two Thunderbolt ports (not Thunderbolt 2, mind) four USB 3.0 ports, an SD card slot, and a headphone jack that can also accept input from headsets. FireWire has been dumped entirely from these newer Macs, but an adapter exists if you still need that particular interface. The optical drive is also out.

|

| The computer is thin around the edges but thick in the back. |

|

| From left to right: headphone jack, SD card slot, four USB 3.0 ports, two Thunderbolt ports, and a gigabit Ethernet port. |

|

| A very familiar keyboard and mouse. |

The presence of two Thunderbolt ports (and the capabilities of Intel's and Nvidia's GPUs) mean that it's easy to connect up to two external displays to the smaller iMac, something that was difficult-to-impossible back when the computers only featured a single mini DisplayPort or Thunderbolt jack. The 12.5 pound weight—about eight pounds lighter than the 2009-through-2011-era bodies—also makes the computer much easier to carry and to tilt on its stand. This stand is stable and reasonably elegant looking, but it's also still limited—you can tilt the display up and down but you can't raise it, lower it, swivel it, or pivot it.

The computer's 1920×1080 display (and the 2560×1440 display in the larger model) looks like the same panel that Apple has been using in the iMacs since they switched to the 16:9 aspect ratio. It's a bright, clear IPS panel that at 102PPI is far from Retina-class, but it still looks decent from what most people would consider to be a normal desktop viewing distance (somewhere around two or three feet away from your face). Colors are bright, contrast is good, viewing angles are accurate, and the glass is much less reflective than in the pre-2012 models. The 2012 and 2013 models fuse the LCD panel with the glass layer that covers it, which is something of a double-edged sword—on the one hand, it enables a thinner display assembly that puts the panel closer to the surface of the glass. On the other, cracking that glass means you're looking at replacing the entire screen, and that's an expensive repair.

|

| Dual microphone pinholes: one on top, one on the back. |

Like the 2013 MacBook Airs, these late-model iMacs also include two built-in microphones that help with noise reduction. Last year we found them to be a modest improvement over the 2011-and-older models' single-mic setups when chatting or using OS X's dictation feature, and this year's iMac performs similarly. Finally, just like last year, the 27-inch iMac is the only model that retains user-accessible RAM slots (it has four, which support up to 32GB of RAM when fully populated). The 21.5-inch has two RAM slots on the inside (capable of supporting up to 16GB of RAM) that can't be accessed without tearing the machine apart, so if you think you'll want the memory eventually you'll probably want to cough up $200 for the upgrade when you buy the computer.

The 2013 iMac's innovations are entirely interior, and there are four upgrades of consequence: the Ivy Bridge CPUs have been swapped for newer Haswell versions; the 6-series Nvidia GPUs have been switched for an Intel integrated GPU on the lowest-end iMac and 7-series Nvidia GPUs everywhere else; the SATA solid-state drives in the SSD- and Fusion Drive-equipped models has been switched for a PCI Express version; and the dual-band 802.11n Wi-Fi has been upgraded to the better-performing 802.11ac.

The CPU

Intel's Haswell architecture increases performance relative to Ivy Bridge running at the same clock speed, but Intel's latest architecture is much more focused on battery life improvements than performance improvements. The huge battery life boost was the most impressive thing about the 2013 MacBook Air and we're hoping for similar gains in the MacBook Pros, but the benefits of Haswell for desktop users are less readily evident (aside from a perhaps slightly lowered electricity bill).

This is the third year in a row in which all the iMacs that Apple offers have come with quad-core Intel processors. Our base 21.5-inch model comes with a Core i5-4570R, which runs at 2.7GHz but can Turbo Boost up to 3.2GHz. The R in the model number indicates both that this CPU includes Intel's Iris Pro 5200 integrated GPU (more on that soon), and that it's not a socketed CPU—R-series chips are all soldered to the motherboards and can't be replaced or upgraded by the end-user. We suspect that the Venn diagram of "people buying iMacs" and "people who upgrade their CPUs" looks like two circles that aren't touching anywhere, but it's worth noting. The higher-end Macs include dedicated graphics and use more conventional socketed CPUs.

Comparing this year's base model to the base models from the last two years, the story is very much the same as last year's: Haswell is a performance upgrade over an Ivy Bridge or Sandy Bridge CPU running at a similar clock speed, but not really so much that you'll notice for most tasks.

The GPU

The graphics processors in most of the iMacs are Nvidia GeForce 700M-series chips like the ones you'd find in laptops. These parts share the same underlying GPU architecture as last year's 600M-series chips, but as we've discussed here, they boost clock speeds enough that they'll generally give you 15-25 percent better performance than comparable last-generation chips.

This isn't true of the low-end iMac that we're reviewing, which is actually a bit more interesting than its more powerful cousins: it uses Intel's integrated Iris Pro 5200 GPU, which makes it the first iMac to use integrated graphics since the low-end 2009 iMac and the first iMac ever to use one of Intel's integrated graphics.

If you read "Intel integrated graphics" and then blacked out from a rage-stroke, stop flipping that table and listen: not all of Intel's GPUs are created equal any more. The Iris Pro 5200 shares its underlying architecture with the HD 5000 that you'd find in a computer like the MacBook Air, but it comes with 128MB of eDRAM integrated into the CPU package that alleviates the memory bandwidth problems that have historically constrained integrated GPUs.

The eDRAM essentially serves as a large cache for both the CPU and GPU—while the GPU still uses the main system memory when it needs to, the cache makes those performance-sucking trips from the GPU to the system memory and back again less frequent. Microsoft and AMD have taken a similar route with the Xbox One, integrating 32MB of eDRAM into the console to help compensate for its slower (but cheaper) DDR3 memory.

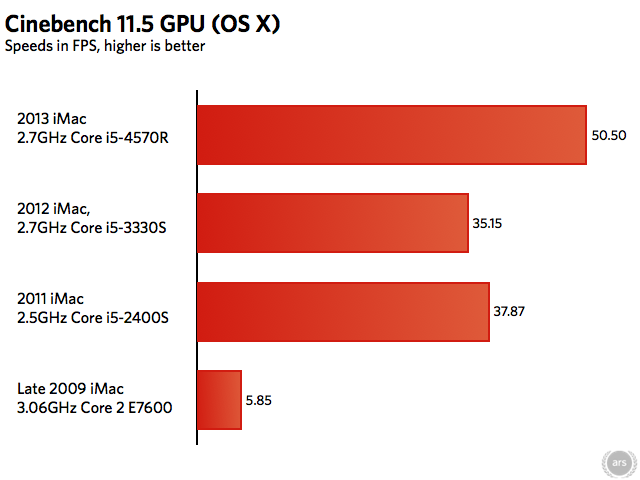

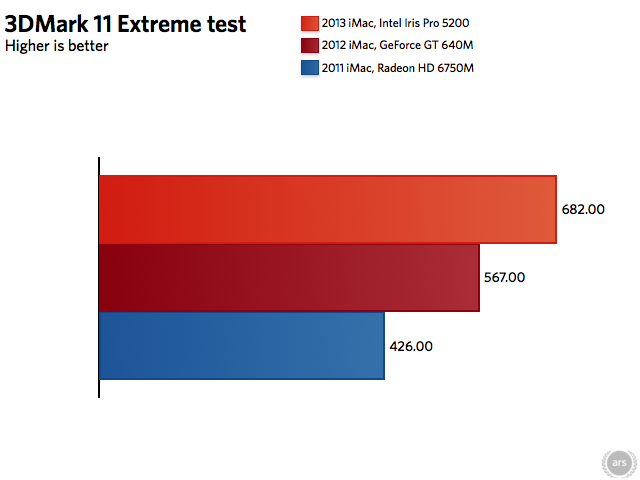

The point is, the Iris Pro 5200 is technically an integrated GPU, but it nevertheless offers performance slightly above the dedicated GeForce GT 640M in last year's low-end iMac under both OS X and Windows 8. We've also provided numbers for the 2011 iMac from last year's review for context, as well as the Intel HD 5000 GPU in the 2013 MacBook Air to show how the Iris stacks up against a more "traditional" integrated GPU.

In the Cinebench test running in OS X, the Iris Pro 5200 does much better than the GPUs in its predecessors.

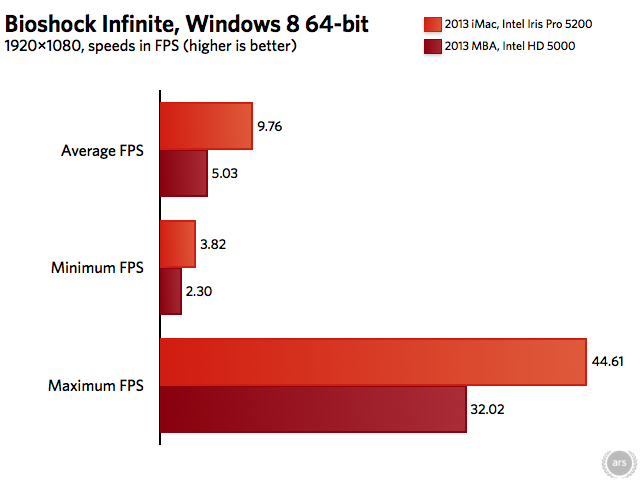

Switching to Windows 8, the Bioshock Infinite benchmark shows that, on average, the Iris Pro 5200 can be as much as twice as fast as the HD 5000. The increased CPU power may also be contributing to this increase, however.

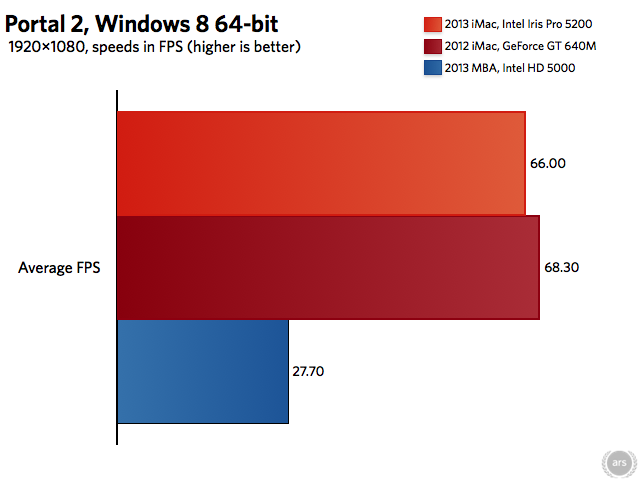

We keep the HD 5000 in the mix and add last year's scores from the 2012 iMac. In Portal 2, performance stays just about level between generations. The HD 5000 is much slower.

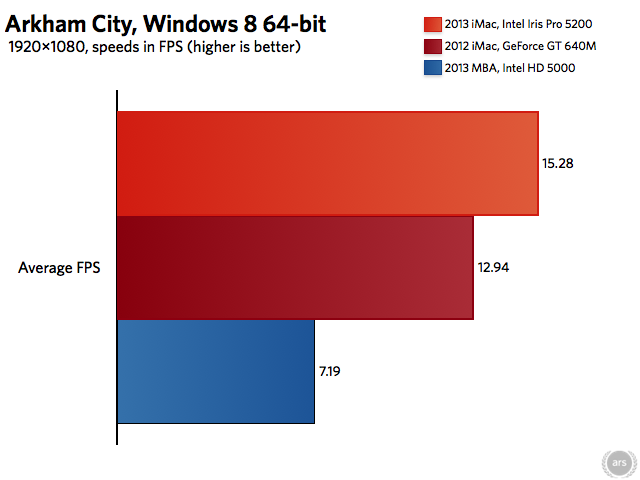

Arkham City (which, like Bioshock Infinite, runs the popular Unreal Engine 3) shows us another game where Intel edges out Nvidia.

Arkham City (which, like Bioshock Infinite, runs the popular Unreal Engine 3) shows us another game where Intel edges out Nvidia.

Like Cinebench under OS X, 3DMark 11 in Windows shows the 2013 iMac outshining its forebears.

Intel's biggest and baddest integrated GPU is usually just barely faster than a midrange dedicated GPU from last year, but that's actually kind of a big deal for Intel. Five years ago Apple was ejecting Intel's integrated graphics from its laptops in favor of better-performing integrated graphics from Nvidia; now the features and performance of Intel's integrated GPUs are good enough that it's starting to replace Nvidia's dedicated chips in desktops. Intel's HD 4000 and 5000 series GPUs (as well as AMD's more recent APUs) have all but eliminated the market for low-end dedicated graphics cards in laptops especially, and while the Iris Pro 5200 has been relatively rare so far, it shows that integrated graphics are only going to continue encroaching on the highest-volume segments of the graphics market.

The Iris Pro 5200's performance also has interesting implications for Intel's Retina MacBook Pros, which are due for a refresh any day now. This integrated GPU's performance is good enough that, in the 15-inch model at least, Apple could potentially get away with marketing the new laptop as having roughly the same graphics performance with much better battery life (both because the Iris would consume less power than the GeForce GT 650M, and because it would free up space on the inside of the laptop that could be used for a larger battery). The graphics performance might actually drop slightly, but the Iris is still enough to drive that Retina display and the benefits might outweigh the downsides from Apple's perspective—something similar happened in the transition between the 2010 and 2011 MacBook Airs, where Apple gave up a little bit of graphics performance in order to give the Airs a huge boost in CPU performance.

At any rate, the lesson for iMac buyers is that despite the move from Nvidia to Intel, the low-end iMac will still give you good 3D performance relative to last year's.

The SSD (and, sigh, the HDD)

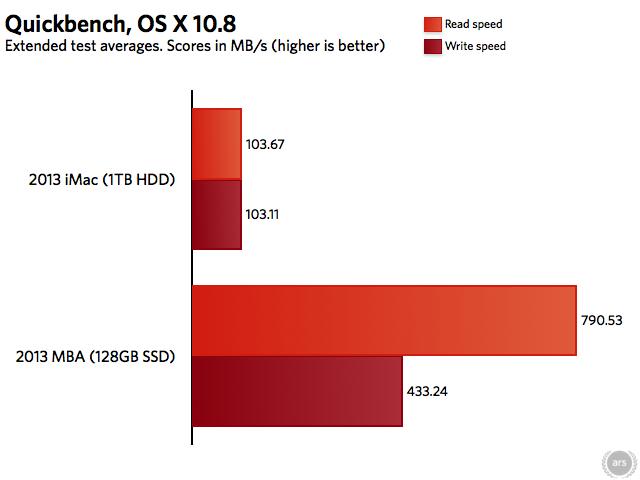

We'll begin with the good news first: for iMacs that come with Fusion Drives and with SSDs, Apple has switched from using a SATA storage interface to using a faster PCI Express interface. Apple already made this jump in the 2013 MacBook Air, and since the company tends to use the same components in all of its products when it can, the performance of SSD-equipped iMacs should be about the same. The standard mechanical HDDs in the iMacs still use a SATA interface—our base model has a SATA II drive attached to a SATA III interface.

The bad news is that all four base iMac configurations, which start at $1,299 and run all the way up to $1,999, ship with standard mechanical hard drives by default. The 21.5-inch models come with 5400RPM drives, while the 27-inch models use slightly faster 7200RPM drives. Prices for solid-state upgrades have come down a bit even if they're still well above market prices (adding a 128GB SSD to the 1TB HDD to make a 1TB Fusion Drive only costs $200 now instead of $250 as before, and a new 1TB SSD option has been added at the high end for a whopping $1,000), but none of these iMacs include solid-state by default, and base models are all that you can walk out of an Apple Store with unless you order through the online store first.

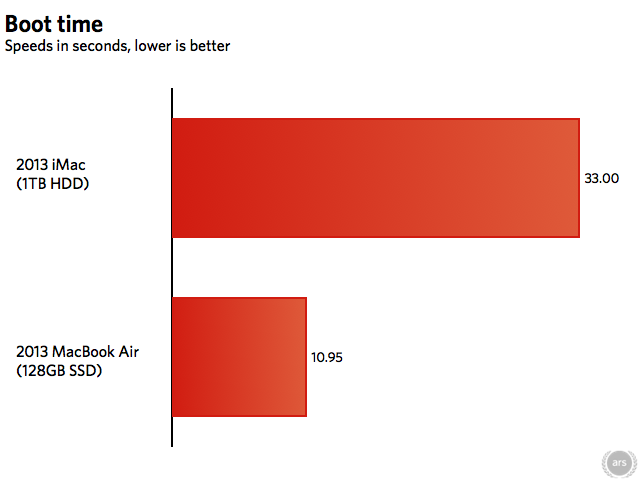

Especially in the 21.5-inch iMac, this decision has a much larger impact on general system performance than the slight CPU and GPU upgrades. You can feel it in everything from boot time to app launch time to file copy time—that spinning hard drive is definitely the performance bottleneck here, just as it was last year. We'll use boot time and the QuickBench performance test to compare the iMac and a 2013 MacBook Air with a PCI Express SSD just to give you some idea of the performance gap we're looking at.

That nice, quad-core iMac is going to be faster for CPU-intensive tasks like video exporting and heavy multitasking, but the MacBook Air almost always manages to feel snappier by virtue of having an SSD.

Why Apple can ship a $999 laptop with 128GB of solid-state storage but can't do the same for a $1,999 desktop is puzzling. Since the introduction of the 2010 MacBook Airs the company has been a big booster of solid-state storage, and yet none of its flagship desktops include it as a default option. It's possible that Apple thinks a large drive is more appropriate for a big, stationary desktop than a small SSD would be, but Fusion Drive is a technology purpose-built to offer customers SSD-class performance with HDD-like capacity. The iMac on my desk has a 1TB Fusion Drive in it that's worked flawlessly for almost a year now, and it rarely feels any slower than my SSD-equipped Air.

It goes without saying that you shouldn't buy any iMac without a Fusion Drive configured, at least. Those upgrades start at $200 for all computers, which raises the base price by a not insignificant amount, but the performance benefits are more than worth it.

1.3Gbps of 802.11ac goodness

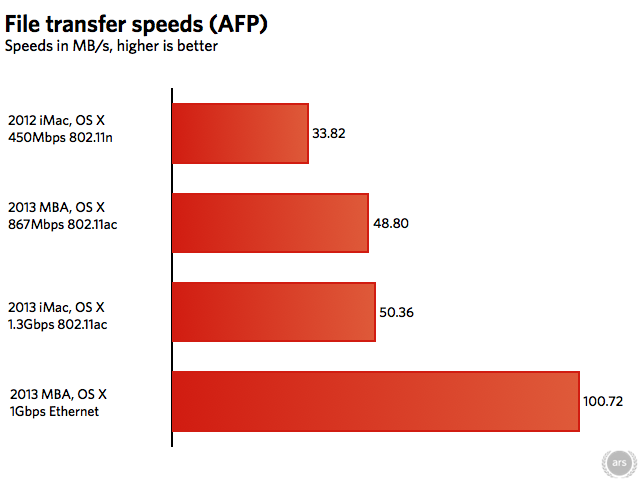

The 2013 iMac is Apple's second product to get the bump to 802.11ac after the 2013 MacBook Air, but we aren't quite looking at the same configuration here. The MacBook Air uses a two-stream (2x2:2) antenna configuration—since a single two-way 802.11ac stream can net you speeds of up to 433Mbps, the MacBook Air can connect to 802.11ac routers at speeds of up to 867Mbps. The iMac uses a three-stream (3x3:3) configuration, adding another antenna for a theoretical maximum transfer speed of 1.3Gbps (the Haswell MacBook Pros, when they're released, should use this same configuration). This is even higher than is possible with wired gigabit Ethernet, though the normal interference and overhead associated with wireless networking means that a wired connection is going to remain the faster and more stable option the majority of the time.

The worst of OS X's 802.11ac issues were resolved in the 10.8.5 update earlier this month, so buyers with capable routers should get a nice wireless speed bump over the 802.11n iMacs of years past.

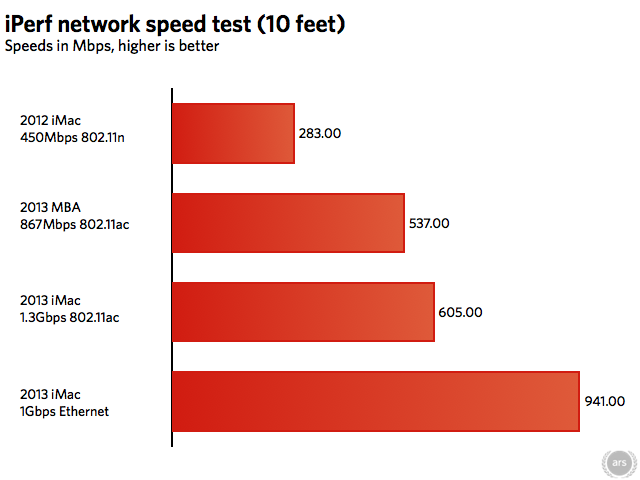

We ran two performance tests connected to our AirPort Extreme Base Station, which is capable of 1.3Gbps connections. The first is iPerf, a network testing which measures raw performance without the overhead associated with a file transfer protocol like AFP or SMB. The second is an AFP file transfer test, in which we transfer one 6GB file using the AFP protocol to give you an idea of best-case file transfer performance. For all tests, the computers are positioned about ten feet away from an 802.11ac AirPort Extreme Base Station with nothing obstructing the signal between the two. In all tests, the computers are connecting to a Mac mini server connected to the AirPort via gigabit Ethernet.

Surprisingly, while the 2013 iMac handily beats the 802.11n adapter in our 2012 iMac, it doesn't really exceed the MacBook Air's performance by much despite the presence of the extra antenna. It could be the case that OS X is still having some 802.11ac-related networking issues, but this seems unlikely—even when the file transfer speeds were being held back, iPerf still performed normally.

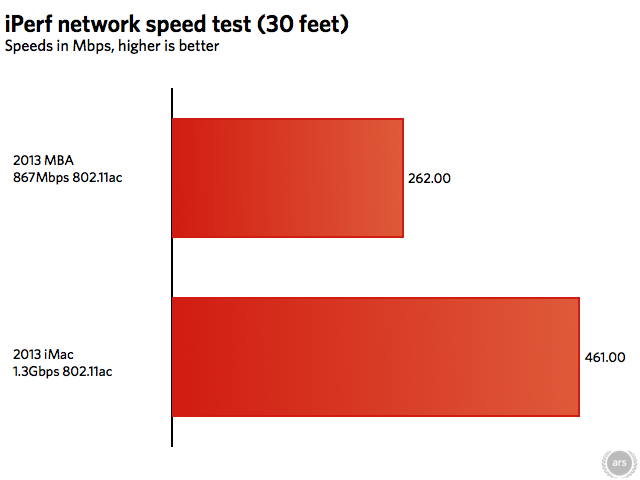

As it turns out, the third antenna in the 2013 iMac is less useful for its maximum possible performance and more for its range. We moved both the Air and the new iMac about thirty feet from the router and put a wall in between them and ran iPerf again.

Here, the iMac's 802.11ac adapter nearly doubles the performance of the Air's. The third antenna is at least a part of the reason, but we'd also bet that the iMac has more room inside it for a larger, stronger antenna than the Air does.

Seriously, spring for the SSD

The iMac isn't a system that you upgrade every year, and its refresh cycle reflects that fact. Every three-or-so years we get a big exterior overhaul, and the rest of the time Apple is content to keep the insides modern without making a big fuss about it. If you liked the 2012 iMac, this year's version is a better take on the same idea. If you hated the 2012 iMac (or certain things about the 2012 iMac, like its reduced upgradeability), Apple has done nothing to assuage your concerns.

Particularly perplexing is the lack of a standard SSD option in an age where most of Apple's laptops include them by default. You can get cheaper and larger SSDs than you could last year and Fusion Drive has proven itself to be a good, reliable way to mix SSD performance with HDD capacity, but even if you're buying the top-end iMac you still have to pay an extra $200 to eliminate the performance bottleneck that the mechanical hard drive has become. Solid-state storage is cheaper than it's ever been, and if there's one upgrade we're hoping for in the 2014 iMacs, that's the one.

The good

- Still a nice-looking, well-built computer

- Fast quad-core processors and nice IPS panels across the line

- Increased graphics performance, even in the Intel-equipped model

- 802.11ac is a nice addition if you've got a compatible router

- Fan noise, heat, and screen reflectivity are all down from pre-2012 models

The bad

- 21.5-inch model doesn't offer user-accessible RAM slots

- No huge performance leaps from last year, which is perhaps to be expected given the maturity of the desktop market

The ugly

- SSDs and Fusion Drives are still add-ons rather than standard options, making these iMacs feel slower than they have any right to feel unless you pay for the upgrade

Courtesy: arstechnica

0 comments:

Post a Comment